Motivating the Majority

Most appraisal and merit pay systems motivate only a small elite while leaving the majority disengaged. True performance comes from systems that reward broad, achievable success, use renewable incentives, and give managers real power to motivate everyone—not just the top 20%.

What Many Appraisal and Merit Pay Systems Do

Companies of all kinds use appraisal and merit pay schemes in the belief that they motivate their staff to higher levels of performance. However, the sad fact is most Company merit schemes motivate only the minority, and effectively turn off the majority. In practice, only the top 20% or so get the best increases. Success is actually reserved for the few. For the rest most appraisals are a fencing match between the manager and the subordinate about how much his performance is worth, with neither relishing the experience. As a result both parties find reasons to defer and avoid the event until the whole business of appraisal becomes just a great administrative hassle.

And these are not the only problems. Many managers perform the appraisal process inadequately, do not ‘tell it like it is’, and often give more-than-deserved awards to avoid confrontation and unpleasantness. Staff who have arrived at the top of their pay scales complain that “they have nowhere to go”. Others – usually good performers in the middle of the scale – protest that some are paid at the top of their scale who have effectively “retired in the job”.

Some years ago Frederick Herzberg demoted money rewards to the status of mere hygiene factors. In his view the true motivators are achievement, responsibility, advancement, recognition and the work itself. But not many companies rely solely on the possibility of advancement or the satisfactions of the work itself to motivate their people. The vast majority encourage achievement with merit awards and give pay increases for taking on greater responsibility. So, despite the research evidence, the actions of most companies tend to confirm their belief that money does act as a motivator.

But do companies direct the money they use to motivate the majority ? For example, many companies use pay scales for managers and office-based staff but use a single pay level for shop-floor employees. Why put an electrician on a straight rate of pay, but put his daughter in the office on a merit scale? Will he not progress through a learning curve just like his daughter, and ought this not to be reflected in his pay? Either he is overpaid at the start, or he is underpaid as his performance improves with experience. Are such companies actually missing a great motivational opportunity by with-holding merit scales from shop floor employees? In most manufacturing companies there are many more manual employees than managers and staff. So are they in fact motivating the minority rather than the majority?

By definition it can only be the few who get the top merit awards and the promotions. The future for most employees, however, is that they will stay at the level they occupy now. Not for them the Herzbergian turn-ons of advancement and additional responsibility. It is difficult to get switched on if promotion is unlikely and second class merit awards are the best you can hope for. But these people are in fact the majority, and if the job of the manager is anything it is getting motivated performance from all employees. Merit schemes which actually pander to the privileged few, and act as a turn-off to the many, simply don’t help the manager achieve that objective.

The Technical Problems

The structure of most merit pay schemes have other inherent problems too. For example, most merit awards are actually added to the current basic weekly or monthly pay. That is costly. An employee on £20,000 per annum with 20 years to go will get around £1,000 from a 5% merit award this year, but the company’s permanent commitment will in fact cost some £20,000 over the period, excluding pension costs. If performance deteriorates next year the increase cannot be taken back – once given, it is there for ever. It has become an entitlement, and once an entitlement it can no longer be motivational. Also, coming as £20 per week or £80 per month it appears small. Paid as a lump sum it would be much more motivating – you can do something with £1,000.

In addition, most pay scales are inordinately long. Generally the top of the scale is typically 30-50% higher than the bottom, and sometimes stretching over a period of fifteen years or more. In many cases the pay scale below may overlap as much as 50% into the scale above, with consequent complaints and comparison problems. Yet it can be reasonably argued that the learning curve for any job is no longer than three years at any level, even for the Managing Director’s job. Long scales also tend to encourage job-holders to expect awards every year irrespective of performance, with the inexorable bunching and drift of even ordinary performers towards the top of end of the scale. Much of this is inevitable – like Everest, as long as the scale is there, people are going to want to climb it! But is this really cost-effective?

Some companies have resorted to defining a limited amount of money which managers can allocate among their subordinates to take care of merit awards. This keeps merit costs to known limits, and forces managers to decide how they are going to award the cash among their people before they start. The focus here, however, is on keeping costs down, not on how best the extra money can produce the extra motivation it is actually designed to achieve. Subordinates still push for the biggest share, and managers protect themselves by saying they are constrained by ‘company policy’, or by making very similar awards to everyone to avoid unpleasantness. One British company recently wanted to encourage better performance among its staff and introduced a new merit pay scheme. The system kept costs down by confining awards to only the top 20% or so. Six months after the introduction, an employee opinion survey showed some two thirds of employees ‘dissatisfied’ or ‘very dissatisfied’ with the new system, with only 19% ‘satisfied’. In effect, the company actually found itself paying out extra money to upset the majority of its staff.

The Negatives of Discrimination

Most appraisal and merit pay schemes make much of discriminating between good, better and best performance. Although this may help to justify different pay awards, comparisons of one individual’s performance against another can set up tensions which make teamwork difficult or create resentments where individuals pay the company back with tit-for-tat negative behaviour.

In practice, discrimination of performance often gives rise to arguments in appraisal sessions. It is relatively easy to distinguish between the top and the worst performers in any department. The hard distinctions are those in between. If the appraisee knows his money will be affected by his classification, he naturally uses every device in the book to exert pressure on his manager to give him the benefit of the doubt. This pressure is hard to resist. If the manager refuses to budge, the subordinate may well be turned off, and get back at the manager by becoming a ‘difficult’ employee. On the other hand, if the manager concedes, he has to face the consequences with his boss and the Personnel Department. This two-way tussle forces the manager to use a combination of persuasion and compromise to minimize his personal aggravation. But the appraisal has then become an exercise in justification, not a process of motivation.

For most people an appraisal is like an examination at school. We all remember that the same people kept on getting the top marks and the prizes – for them it was fine. For the majority, however, the examination marks were simply a repeated confirmation of their mediocrity. With them, examinations generated feelings of anxiety and worry. They feared the worst. And these are precisely the feelings appraisals generate in most people at work. That is why appraisals are constantly put off and avoided by both managers and subordinates. Discrimination ensures that only the few can really call themselves a success, and the rest become also-rans.

The Key to Motivating Employees on a Wide Front

Why is all this time and effort spent in such fine discrimination if it does not make a positive contribution to motivating employees? For the fact is, merit awards based on appraisals of last year’s work can only be reward for performance past. But true motivation is the heightening of effort and attention in anticipation of rewards yet to come. And that must not be only for the few – it must motivate staff on a broad front. The key to motivating employees throughout the organisation is the prospect of success for the majority. Only when everyone feels they can succeed in your business, will they start delivering that elusive extra performance which is the whole purpose of the exercise. And that extra performance can be considerable.

For many years management consultants made a very good living out of the fact that employees with effective methods and a financial incentive produce measurably better results than those without. First, the consultants would devise the most effective methods they could for doing the work involved, train the employees in the new methods, insist that they used them, and provide a money incentive for hitting predetermined targets. As a rule of thumb, they assumed that employee performance would be around 75 before the incentive scheme was in operation, and would rise to 100 following its introduction. The difference is rather like a normal walking pace compared to the brisk pace of someone on his way to catch a train. In other words, from the same people ‘motivated’ performance was expected to deliver some 33% more output than ‘normal’ performance.

Productivity – making more effective the resources under one’s control – is actually the central task of management. Consultants would say there is a third more to come from people who feel motivated. Peters and Waterman, in In Search of Excellence, go a lot further than that : “The amount of performance improvement possible from the turned-on team is not a percent or two here and there, it’s hundreds, if not thousands, of per cent”. However much it is, it is well worth going for. And not just from the high-flying few. We want that sort of performance from whole teams of employees, from the great majority rather than the minority.

What Is Required

Schemes which are designed to use money awards to produce enhanced or motivated performance from the majority of employees need to fulfil a number of important requirements.

- They should motivate on a broad front i.e. encourage everyone to stretch, and expend that extra effort.

- The money incentive should be endlessly renewable i.e. not die out when individuals reach the top of their scale.

- The money should be paid as lump sums.

£1,000 paid as one lump is much more motivational than £20 per week. - The winning posts need to be made crystal clear.

Appraisals which depend on subjective assessment of personal qualities will always cause inconsistency and argument. Better to pay the money for the achievement of defined, stretching objectives. - The system should encourage the holding of appraisals.

- It should avoid demotivation.

Stating the requirements of a system tends to be a much easier task than turning them into practical, workable realities. But the prospect of having a ‘turned-on’ many, rather than a motivated few, is a prize worth pursuing. Here are some practical and tested ways of implementing these concepts.

Use lump sums

If it is true that people respond to the prospect of financial rewards, then merit awards paid as lump sums are far more motivational than the same amount of money paid in small instalments in salary over the year. Despite the tax take, the net amount is still more desirable than the amount left when added to regular salary. If the lump sums are also paid out at useful times in the year – before holidays or before Christmas, for example – then even better. Of course, it makes a difference to your company cash flow if merit awards are paid as year-end bonuses rather than being spread out over the year, but there is no doubt what the recipients prefer. And that means a lot more motivation for the same money, more bang for the same bucks.

There are other advantages too. When a merit award is added to salary it is a permanent increase. The true cost to the Company is actually the yearly amount times the number of years the employee remains with the Company – you could be multiplying the yearly cost by 20 or more. Paid as a lump sum, however, you incur only the costs of 5% of this year’s salary, not of every salary for years thereafter. That same lump sum can be awarded again next year, of course, but only if the motivated performance of which the individual is capable is actually demonstrated next year as well.

In this way the award is made annually renewable. No employee will ever get to the top of their scale again and have nothing else to go for. Every year there will be something worth stretching for – for every employee, not just for some. Managers at every level will have the opportunity to agree sensible and demanding targets with their subordinates, and expect to get motivated performance from every one of them. That means motivating the majority, not the minority.

Finally, merit awards paid as lump sums are not added to basic rates of pay. That means they are not added to other costs such as holiday pay, sickness benefit, overtime costs, and the rest, for the whole of the year thereafter. Staff budgeting becomes a much more predictable process – a change that will be welcomed both by managers and accountants.

Use Short and Simple Pay Scales

There is a great tendency for pay arrangements to try to take account of everything, and therefore to become complex and confusing. It takes real effort and commitment to keep them simple, but the benefits of the simplicity are appreciated all around the Company, both by management and employees. The use of lump sums as merit awards gives the opportunity for such simplicity with the introduction of much shorter learning curve pay scales.

On the basis that even the M.D. of the company should take no more than three years to reach a competent standard in the job, pay scales of this length can be introduced for jobs at every level. Every new entrant to a job would start at the beginning of, say, a three-year scale, and move in equal steps up the scale each year, providing satisfactory progress was being achieved. It would be expected that 80% or more of job-holders would in fact make such satisfactory progress (as experience shows they do).

Of course the judgment of the manager would have to be exercised in coming to this conclusion. In the case of insufficient progress, he would have the authority to defer the increase, or with-hold it, as appropriate. When increases depend on his authority, subordinates tend to listen better and respond to his standards. He in turn would have to make clear from the beginning precisely what is expected, but from observation this would be no bad thing in many Companies.

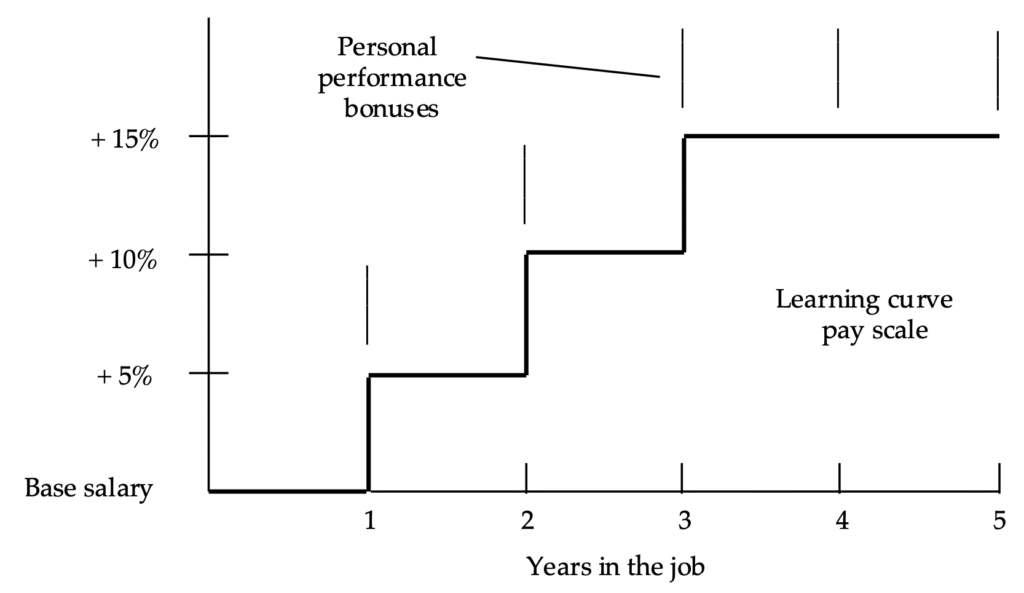

A 15% pay scale, combined with opportunities to earn lump sum performance bonuses, would then look something like this.

Abandon Discrimination

This is a key point in the business of motivation. In the normal run of things, performances of subordinates will fall into a normal distribution pattern, with a few at the good and bad ends of the performance scale, and the majority falling somewhere around the middle. If the objective is to reward performance past, then rewards should follow a similar distribution curve, and comparing and differentiating performances will be necessary. However, if motivating the majority is the objective, discrimination is simply self-defeating.

We are never going to make a silk purse performer out of sow’s ear material. What we can do, however, is to move each employee up one or two notches on the performance scale which represents the best performance of which they are capable. The best any Company is ever going to do is to get everyone performing at his or her ‘personal best’. You cannot do any better. And if you believe, as many affirm, that your people are your most valuable assets, then getting the best they can each deliver becomes a task of paramount importance.

In practice, every manager should agree with each subordinate key objectives which, if achieved, will constitute ‘stretch performance’ for that employee. A sufficiently attractive personal performance bonus – the prospect of two weeks’ pay paid as a lump sum will motivate most employees – should then be payable for the achievement of these key objectives. Any employee who delivers on these should get all the money. Normally the majority (around 80% or more) will. That way the majority will begin to feel a success in your business, rather than some kind of mediocrity. And there is nothing so motivational as the drug of success . . . .

A few words of warning. It is important that not all employees get the money, otherwise the money will be simply seen as an entitlement and no longer motivational. It has to be genuinely for extra performance. Failure to meet the agreed key objectives should not get the money, not any of it. Do not be persuaded to start differentiating again ‘to keep people happy’. At the very worst give half of the money for a ‘near miss’, or defer the award to sometime in the following quarter if a little more time will allow the person to deliver. But insist on real performance – after all, that is what the Company is actually paying extra for.

Give Power to Your Managers

It is not just money that motivates. One of the most important factors in getting motivated performance from all employees all the year round is the immediate boss. Personnel Department cannot do it from afar, it has to be done by the person who interfaces with the employees on a daily basis – the manager. No matter how good the system, it is how it is used that counts. That is why managers have to be a committed and integral part of the system, or it will simply not work effectively.

As a first step, managers have to be educated about the purpose of the appraisal / reward system i.e. to get motivated performance from all employees, to get them giving their ‘personal best’. The money will not do it by itself, they have to add the strength of their management and coaching all the year round to the motivating force of the reward.

Secondly, a lump sum merit award system gives managers considerable power. Employees tend to listen much better to their manager during appraisal sessions when they know he has one or two weeks’ pay, which he can award or not, based on their level of motivated performance. If employees know they can expect a personal bonus for meeting their agreed prime objectives, around 80% of them will actually be looking forward to their appraisal, knowing, without their boss having to tell them, that they have already passed the winning post. And the appraisal also gives the manager a golden opportunity to raise all these other questions of attitude, style, compatibility, and co-operation which are so important to good teamwork. Used well, such a system can be a powerful tool in the hands of the manager.

It is useful before embarking on appraisals each year to get the managers involved together in working groups to discuss the sort of objectives they are likely to agree with their subordinates. This will lead to a degree of consistency between managers in objective setting, and enable them to learn useful practical tips from each other. The act of getting together also reinforces with managers the importance of continuing to motivate and manage their people well as an integral part of their job. Meeting again after the appraisals is also helpful on a post- mortem basis to discuss the problem issues and build the learning points into the following year’s procedures.

If there is a Personnel or Training Department, one of their useful functions is to attend such meetings to help the practising managers with their everyday problems. It must be added that the task of coaching, appraising and motivating must remain firmly the job of the manager and not of the Personnel Department. Managers will of course make mistakes. Personnel Departments do too. But persistence and patience should be exercised in allowing adequate time for managers to learn this part of their job well. When they have finally taken on board this daily and ongoing responsibility, that patience will be well rewarded.

Conclusion

Any manager knows, and consultants have been proving for many years, that there is a substantial difference between ordinary performance and motivated performance. Yet most appraisal and merit pay schemes tend to motivate the elite few and leave the majority feeling like ordinary also-rans. In most companies, there is a wealth of motivated performance which is just not being released. That is an increasingly untenable situation for most companies in today’s tough and competitive world. The vast potential available in motivating the majority of employees will put those companies who tap into it successfully in quite a different league to their ordinary competitors.